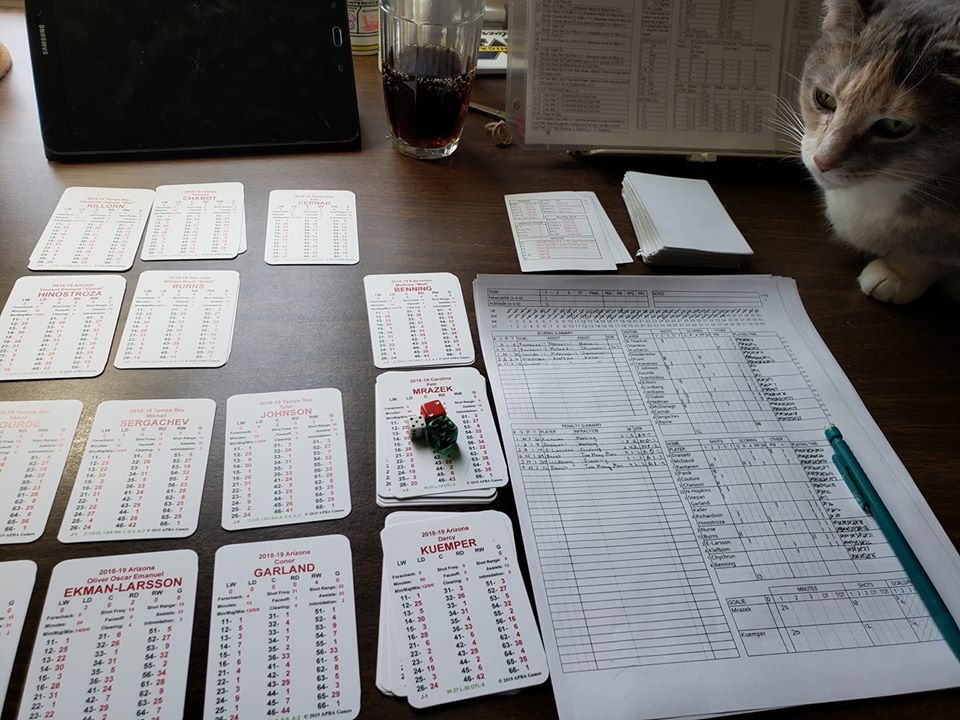

In the mid-60s, the APBA Game Company introduced their basketball game to join their product line. It was very accurate, you actually determined passing before shooting and could strategically move offensive and defensive players across the court. It was also an absolute slog to play, a simple 24-second sequence could take over a minute to play, not to mention all of the math necessary to make new finder tables every time a substitution was made. Multiply that by 200 plays and a single game could take over six hours.

So, APBA later released “super basic” or “short game” rules. These eliminated the dribbling and passing, and laid to game bare to simply doing the shooting and rebounding. Still, each play sequence would take at minimum four dice rolls, which means still 800 dice rolls at minimum, and this would cut the game to four hours.

In 1993, they introduced a new game that eliminated the laborious finder tables. I don’t remember much about this game, I only played it once. Not sure why this game didn’t hold on like the hockey game did, a few seasons were released, and the game was quietly retired.

During the pandemic, I toyed with the idea of making an APBA-style basketball game. I made cards, and charts, and ran a few simulations. It worked OK as a board game, but to be honest I put it aside because frankly I’m not much of a basketball fan, and the interest was just not there.

However, the idea still stuck in the back of my head, and I thought about what it would take to make a reasonable game. My idea was basically to have fast action cards like you see in the soccer game to determine shooters, zones, rebounds, etc. I would not make any cards, it would work on the existing card sets out there, which did limit to what I could do.

My first attempt looked good in theory, but it did not play well. It was too much staring at cards to look at ratings and the game didn’t flow like I had hoped, and gave up playing the game after the first quarter. So I had to simplify it even further.

My second attempt worked much better, using a lot less of card staring and I was able to play a full game in two hours and ten minutes. The 1989 Pistons defeated the 1989 Lakers in a thrilling 90-89 game.

The game boils down to using two types of action cards, one for determining the shooter, and one for determining everything else. For the most part, the dice are only rolled when looking at the player’s card.

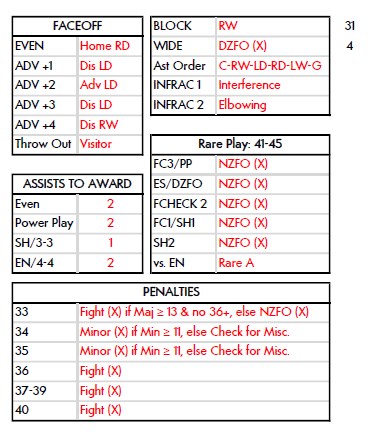

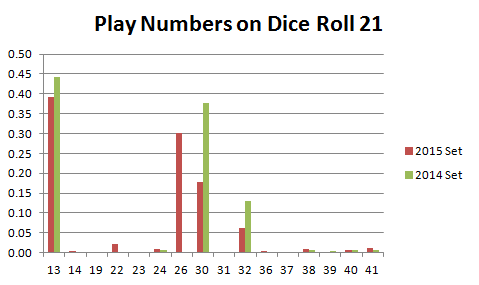

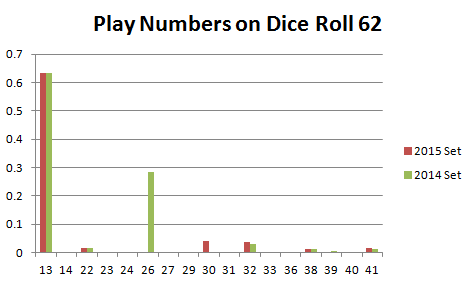

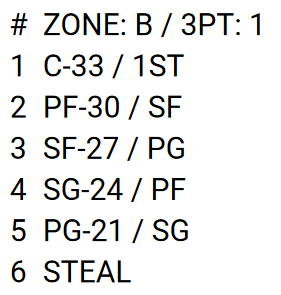

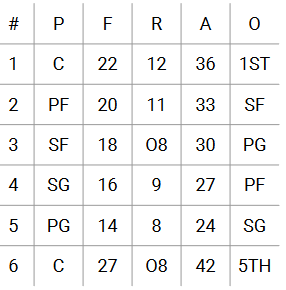

Before a quarter, a single die roll determines which row will be used for the entire quarter. The shooter is then determined by the card. For example, if the point guard’s shooting rating is 21 or greater, that player would be the shooter, otherwise the shooting guard would take the shot. Post shot, you would draw an “Everything Else” card an determine if you would need to check for the fouler (F), rebound (R), or assist (A). This card works in the same way as the shooter card – find the appropriate rating for the position on the left and if the rating isn’t high enough, use the position in the right-most column. It’s really that simple.

So for now this will be an “open source” game, I am willing to provide the rules, charts, and action cards for free. There are 14 links below, one for the rules, one for the single play chart, six for the shooter cards and six for the “everything else” cards. Simply cut the action cards, find a set of APBA basketball player cards, and you’ll be playing in no time.

If you end up playing a game or two, I would love to see your scoresheets so I can collect play-testing data. I’m curious on how well the game plays. Have fun!

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Rules.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/PlayChart.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Shooter1.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Shooter2.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Shooter3.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Shooter4.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Shooter5.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Shooter6.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Assignment1.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Assignment2.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Assignment3.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Assignment4.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Assignment5.pdf

https://www.mikeburger.com/apbahoops/Assignment6.pdf